Australian Financial Review

Commonwealth Bank boss Matt Comyn says policymakers need to be alert to the dangers of ceding important industries to global tech platforms without scrutiny.

This week, Matt Comyn wasn’t pulling any punches. The Commonwealth Bank chief executive used his appearance at The Australian Financial Review Business Summit to attack the market power of Apple and other digital platforms.

“One of the things that I find extraordinary is the lack of scrutiny, across some of the tech companies, in particular, which have large businesses in Australia,” Comyn said. It was a comment that came in an environment where the major banks – and more recently, supermarket chains – have been under significant political pressure for their big profits.

After detailing Apple’s much larger margins, and much smaller contribution to the Australian tax take, Comyn described the technology giant as the “undisputed world champions of Kabuki theatre”. They should be subjected to “a lot more scrutiny”, he said.

Beneath the one-liners – Kabuki theatre is a highly stylised form of Japanese performance art – Comyn’s commentary reflected an elevation of a three-year public fight with Apple against its growing influence in the financial sector. Apple, as he sees it, is a new gatekeeper to the payments system.

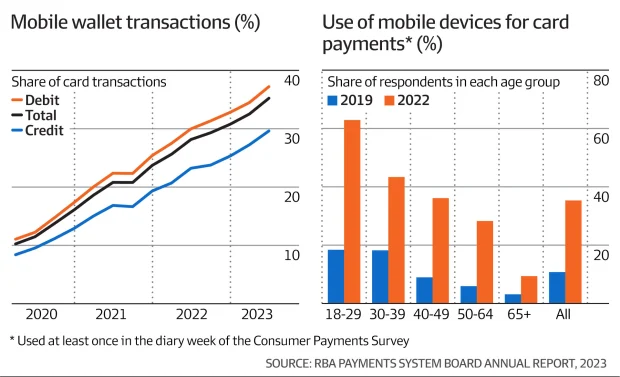

As paying with mobile wallets on smartphones surge to more than one-third of all Australian card payments, Apple is clipping banks’ payment fees, one frustration for Comyn and other bank bosses.

Apple is probably making around $130 million a year from the banks as more payments are pumped through iPhones. Furthermore, it controls bank apps’ access to tap and go technology on iPhones, restricting customer engagement with banks’ proprietary mobile banking apps.

Not just banks

Yet, this week, Comyn reframed the debate as one going well beyond CBA’s self-interests. He made a plea for another Team Australia moment. He wants Canberra to start viewing Apple’s move into banking similarly to Meta riding roughshod over the Australian media.

The call for more scrutiny of big tech is necessary because Australia risks ceding some control over critical national services. It’s not just Apple. Meta has poked the media in the eye by cancelling a government-brokered deal to pay for content. Google is making moves into digital identity. Amazon is growing in retail.

Comyn pitched a discourse on Australia’s regulatory perimeters as one of fairness. Are we unwittingly tilting the playing field against our own corporate giants in favour of even bigger foreign companies and their sophisticated teams of global lobbyists?

Comyn is not alone in calling for urgent elevated scrutiny of big tech. Australian Competition and Consumer Commission chairwoman Gina Cass-Gottlieb, writing in The Australian Financial Review last month, said she was “surprised that the public conversation about competition often skips over the market power of the digital giants, whose products and services are now a virtually inescapable part of our lives and livelihoods. Their expanding presence is impacting our cost of living in many ways that are often undetectable.”

‘Unfairly high’ earnings

Ross Buckley, who is chairman of the digital finance advisory panel at ASIC, believes that the income Apple is earning for hosting payment cards is too high.

“Its wallet is just a representation of a card; it is banks that take the credit risks and actually move the money. Apple’s earnings appear unfairly high compared to what banks do,” says Professor Buckley, who researches financial services and payments at UNSW. The biggest threat to the banks from Apple, he says, is that it takes over the interface with customers without being subjected to existing laws.

This could leave banks in the back end, bearing the burdens and costs of banking regulation but less of the profits. It’s a nightmare scenario for bankers, and one keeping Comyn awake at night.

“This is the thin edge of the wedge,” Buckley says. “Apple will not stop with payments. In the future, a customer might go through Apple for a home loan, provided by one of the banks.

“But if Apple’s interface goes down, that could cause consumers to lose confidence in the bank providing the product or the financial system. So, we need to think differently about the regulatory perimeter and the entities that fall within it. ”

Global banking leaders are eyeing Apple with caution. JPMorgan chief executive Jamie Dimon told the same Summit that Apple’s entry into the provision of buy now, pay later was evidence of growing competition between big tech for retail banks.

In the United States, BNPL loans are being made from Apple’s own balance sheet. Under an arrangement with Goldman Sachs, it is also offering credit cards and a savings account. In the United Kingdom, Apple has launched a new product that aggregates regulated bank accounts in its mobile wallet.

For its part, Apple says it is only playing an outsider’s role in the Australian payments system. It describes Apple Pay as a “payment presentment method” – essentially a technology service to banks. “Apple only has an indirect and very limited, peripheral role in the payments system and any assessment of Apple Pay’s role in payments needs to be grounded in fact. Apple Pay poses no financial or operational risk,” it has told a parliament inquiry.

Building a regulatory response

But international regulators are slowly waking up to its growing clout in financial services. The European Commission said in January that Apple enjoys significant market power in the market for smart mobile devices and holds a dominant position in mobile wallet markets on its iPhone operating system. It has forced Apple to make a commitment to allow European banks to access the “near-field communication” chip on the iPhone to process payments outside Apple’s wallet free of charge for at least the next decade.

Australia is in the process of developing its response. Changes to payment rules that would allow the RBA or the government to classify Apple Pay and Google Pay as a payments service are stuck in the parliament after being proposed in 2021. The powers would allow the RBA to collect data from Apple, and potentially intervene in the market to ensure its fees and access rules are fair.

Two days after Comyn’s comments, RBA’s head of payments, Ellis Connolly, told an industry event that regulators were closely watching Europe’s interventions, and the RBA is ready to act once the new payment laws pass parliament.

“We will be particularly keen to see what impact it has on competition in the EU market. We will be keen to learn any lessons we can from that for Australia,” he said.

Furthermore, the “remarkable take-up” of mobile phone payments “has raised some competitiveness and efficiency issues”, and the central bank, when it gets its new powers, will consult on “whether there are any interventions required to support competitiveness and efficiency in the market,” Connolly said.

Apple rejects the new powers, describing them as “not a proportionate nor evidence-based regulatory response for services that are simply a digital presentation of a physical card, like Apple Pay, given Apple Pay’s indirect and limited role in payment systems and the lack of any material risk that has been identified as being caused by Apple Pay.”

Australian Banking Association chief executive Anna Bligh agrees with Comyn. “With payments through mobile wallets skyrocketing to $93 billion per year, it’s critical these transactions are subject to the same oversight and consumer protection laws as the rest of the payments system,” she says.

Comyn told the Summit that the approach of big tech in Canberra was “completely different to the attitude of Australian corporates”.

“I read the prime minister’s comments recently with Meta’s decision [to pull out of its media funding deal], where he said it’s not fair that companies are able to benefit from the investments, in either infrastructure or people, and to take advantage of that … Clearly that could be, in my view, applied across a number of different industries, not the least of which, is banking.”

Buckley says the executives at the tech firm should be appearing before parliamentary committees more often, so legislators can gauge their intentions for themselves. “The big four banks go to parliamentary committees each year; why not the big tech companies? Parliamentarians should have the opportunity to put questions to Apple and Google, Facebook and Amazon,” he says.

“Look at the influence these platforms are having, not only in payments, but in media and on American democracy. It is incontrovertible that there should be more parliamentary oversight in Australia.”

Former treasurer Josh Frydenberg told the Summit this week that governments would need to engage more aggressively with big tech firm chief executives to defend the national interest. He had more than a dozen conversations with Facebook (now Meta) chief executive Mark Zuckerberg during negotiations for the media deal in 2021, and several with Google chief executive Sundar Pichai.

“Apple’s advantage is it doesn’t think of itself as a financial services company but as a data and tech company – but that is also what banks are,” Buckley says. “Electronic money today, after all, is merely data. Most banks look at each other as the competition because they are thinking about the next few months. Over that short timeframe, that might be right. But over the next three or five years, the competition will be the companies that dance well with data, like Apple and Google and Facebook.

“And these big techs tend to squeeze out competition: it is an area where ‘the market’ doesn’t operate well, because of the network effects of a popular technology.”